Plan Recommendations

To carry out the goals of the management plan will require adopting over 50 recommendations on planning, education, stewardship, funding and management and restoration.

- Introduction

- Background

- The Recommendations

- Planning

- Education/Stewardship

- Best Management Practices/Restoration Sites

Introduction

How do we limit our P in the future?

Having determined current phosphorus (“P”) loadings in the subwatersheds and having set a goal to limit or reduce future nutrient inputs, the MPSB Subwatershed Advisory Committee identified management techniques that would stabilize phosphorus concentrations, make landscape improvements to limit phosphorus loading, and reduce existing sources of excessive phosphorus.

The list of management techniques presented below is by no means comprehensive; as the plan evolves, it is likely that some strategies will be eliminated or revised, many implemented, and others added. The recommendations developed by the MPSB Subwatershed Advisory Committee can be placed in four main categories:

- Planning

- Education/Stewardship

- Funding

- Best Management Practices/Restoration Sites

Background Return to Top

During plan development fifty-eight (58) strategies identified by the committee were ranked according to the following criteria;

- Positive impact on water quality

- Degree of effectiveness

- Ease of implementation taking into account cost, social acceptability, and legal requirements.

The ranking system was based on high, moderate or low, using a “3†to indicate high or good, “2†for moderate or fair, and “1†for low or poor. The highest possible score was a “15â€. While some strategies might have a greater positive impact on water quality, and be more effective, high cost, or difficult legal requirements and/or questionable social acceptability could lower the score.

The Recommendations Return to Top

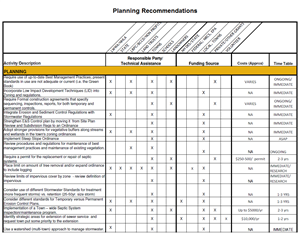

Planning Recommendations (PDF, 66kb)

click above for the full 6 page PDF document

or click here for the Excel file (XLS, 69kb)

In addition to having a positive impact on water quality, effective management techniques should be achievable, foster stewardship, and take funding requirements into consideration. For the 58 actions chosen by the committee, an implementation strategy was developed identifying responsible entity and/or technical resources needed, potential funding sources, costs, and timetable.

PlanningReturn to Top

Sixteen (16) planning strategies were identified, most of which will be the responsibility of the Planning Boards in each community to implement.

Planning activities received high rankings due to the low cost and few legal obstacles associated with implementation. Some of the actions can be considered “housekeeping†items, such as “integration of Erosion and Sediment Control Regulations with Stormwater Regulationsâ€, and “strengthening the E&S Control Plan by moving it from Site Plan Review and Subdivision Regulations to an Ordinanceâ€. Others address increased pollutant load associated with landscape change; by incorporating low impact development techniques into zoning and regulations, and requiring the use of best management practices, planning boards represent the first line of defense in protection of the lake’s water quality.

Education/Stewardship Return to Top

Under Education/Stewardship, two out of the ten (10) strategies recommend better communication and cooperation within and between communities. Several strategies target educating residential homeowners on septic systems, landscaping, and the importance of maintaining stream buffers. As residential land represents the largest percentage of urban land use in the study subwatersheds, management measures that target individuals and result in behavior change could have a significant impact in lowering pollutant loads.

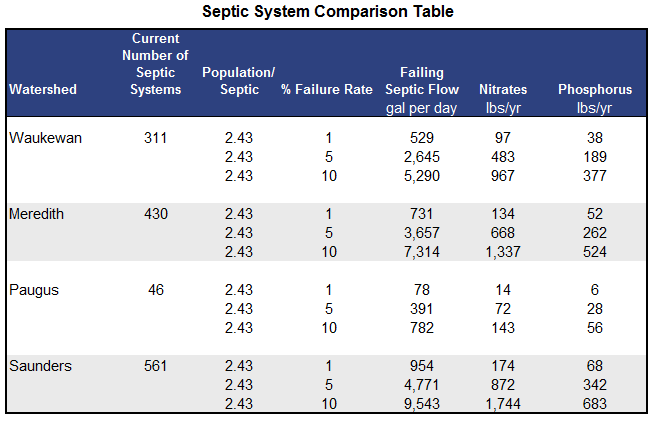

Impacts from failing septic systems are one of the top concerns identified by the communities. According to EPA, failure rates for septic systems typically range between 1 and 5 percent each year but can be much higher in some regions (See here for further information from EPA). The table below presents a comparison of the potential impacts from failing septic systems for all four subwatersheds at various failure rates. The results were calculated using the STEPL (Spreadsheet Tool for Estimating Pollutant Load) model.

Future development in these subwatersheds could significantly impact potential pollutant loads from increased numbers of on site wastewater treatment systems, unless expansion of the Winnipesaukee River Basin program occurs.

Future development in these subwatersheds could significantly impact potential pollutant loads from increased numbers of on site wastewater treatment systems, unless expansion of the Winnipesaukee River Basin program occurs.

Best Management Practices/Restoration Sites Return to Top

One of the objectives stated in the goal statement is to reduce existing sources of excessive phosphorus.

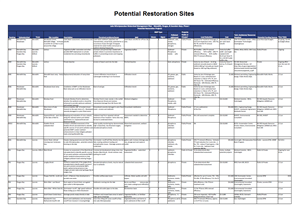

Potential Restoration Sites (PDF, 47kb)

click above for the full 2 page PDF document

or click here for the excel file (XLS, 45kb)

Some of the sites noted include:

- In the Lake Waukewan subwatershed, 3 sites were identified as needing detailed site assessments in order to determine specific sources of nonpoint pollution and potential bmps: Monkey Pond, Saywood Brook, and Reservoir Brook.

- In Meredith Bay, Hawkins Brook is the stream of major concern, flowing through and along the commercially developed Route 3, then into a large wetland before flowing under Route 25 into Meredith Bay. Read the preliminary site assessment for details on this site.

- Two streams located on the eastern side of Paugus Bay were listed as in need of detailed watershed assessments: Black Brook and Langley Brook. Black Brook which begins at Lilly Pond in Gilford, flows in a westerly direction crossing under Route 11 at Walmart, and continues along the south side of the commercially developed highway. At the junction of Route 11 and Union Ave., the brook flows behind CVS and continues behind the commercial properties on Union Ave. before once more crossing under the road to outlet at Spinnaker Cove. Tributary monitoring conducted on Langley Brook has shown higher than average phosphorus levels. Most of the area upstream of the brook is forested or residential development; therefore further study needs to be conducted to determine whether the higher phosphorus levels are natural or related to human activity.

Other instances such as streambank stabilization of known erosion sites proved easier to quantify. Gunstock Brook in Gilford is the major stream emptying into Saunders Bay. Stabilization of the four erosion sites identified along the brook would reduce the annual sediment load to the brook by 149 tons, and the phosphorus load by 131 lbs.

Vegetative buffers along roadways, streams, and the shorefront offer one of the most cost effective strategies in limiting pollutant load to surface waters. The following phosphorus removal efficiencies were determined for various roadway buffer widths based on the method outlined in the NH DES Watershed Management Bureau memorandum “BMP Removal Efficiencies for TSS, TN, and TP” dated 5/24/2007.

REPBW = [(PBW-10) x RET]/(IGBW-10); where:

REPBW = Removal Efficiency (%) for the proposed buffer width

PBW = Proposed buffer width

RET = Removal Efficiency in % from the BMP Removal Efficiency Table (refer to: NH Stormwater Manual, Vol. 2, Appendix B)

IGBW = Buffer width in feet per NHDES “Interim Guidance” (80 ft. is used for roadway buffer)

- 40 ft Buffer – 19% removal efficiency

- 50 ft Buffer – 26% removal efficiency

- 80 ft Buffer – 45% removal efficiency

Actual load reductions realized depend on the length and width of the buffer installed. For example, maintaining at least a 50 ft buffer along the 6.4 miles of Gunstock Brook in Saunders Bay would prevent an estimated 29 lbs of phosphorus and 16 tons of sediment from entering the brook each year.

Management measures that implement best management practices on roads can be effective in reducing pollutant loads. In the three subwatersheds studied, the road network acts as a vehicle or transportation mechanism for untreated stormwater; carrying runoff to catch basins and storm drains which in turn empty directly into the lake. Catch basin retrofits are recommended for off line systems; each deep sump catch basin is designed to treat 0.25 acre, and is effective mainly at removing total suspended solids. Areas such as Waukewan Street in Meredith, and Weirs Blvd. along Paugus Bay have numerous catch basins and storm drains which collect stormwater and outlet directly to the lake.

Explore potential restoration sites in the plan area using our interactive map.

Top photo by Dimitri Sokolenko